In a major new retrospective at London’s Royal Academy, one painting commands an entire wall and, arguably, the entire room. Kerry James Marshall’s School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012) stretches nine feet high and thirteen feet wide, a monumental canvas that both towers over its viewers and invites them closer. To stand before it is to feel engulfed by color, movement, and coded meaning.

“It can be seen from about 60 meters away,” notes art historian and curator Mark Godfrey, who organized Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, the largest European survey of the artist’s work to date. “If you want to make a painting that many people can look at together and that can compete with paintings in big museums, then it’s got to have scale. The painting has its own wall—it’s almost architectural.”

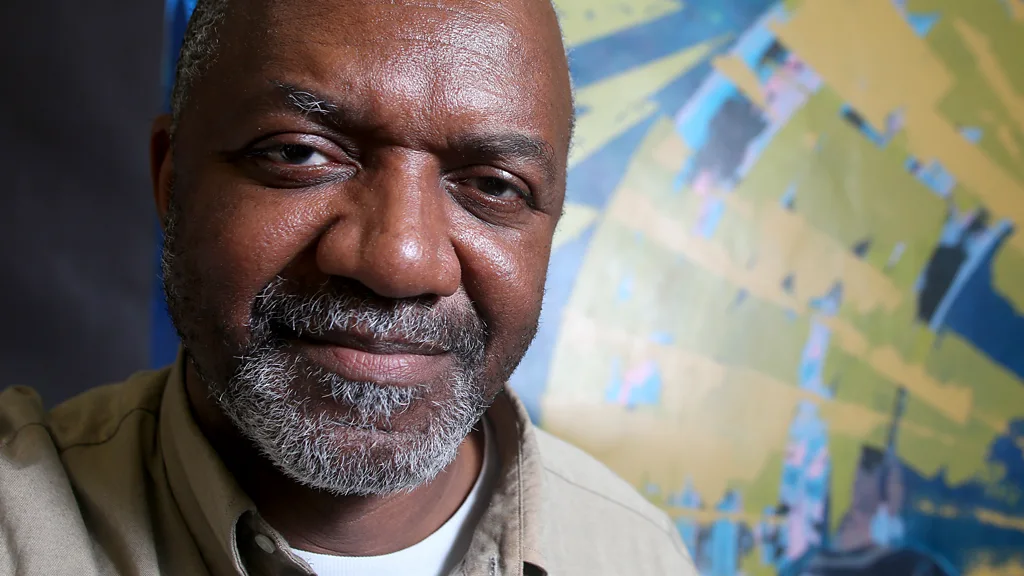

The US figurative painter is among the most acclaimed living artists today. In 2018, Marshall broke auction records when his painting Past Times sold for $21.1 million—a groundbreaking figure for a living African American artist. Critics have lavished praise on the Royal Academy exhibition, calling it “staggering,” “ingenious,” and “astonishing.” One reviewer urged, “Prepare to be bewitched.” And nothing in the show bewitches more than School of Beauty, School of Culture.

A Scene of Everyday Life—Transformed

At first glance, the painting seems simple: a bustling Black hair salon somewhere in America. Women laugh, talk, and pose as children play at their feet. In one corner, a stylist leans over a client in mid-gesture. Off-center, a woman in a yellow-and-black shirt and striped trousers fixes her gaze on us. Her stance—a bent knee, one hand on her head, the other on her hip—suggests both casual self-assurance and performance. It’s a scene anyone familiar with beauty salons can recognize: a place where appearance, identity, and community intersect.

But, as with much of Marshall’s work, the everyday masks deeper layers. “He will refer to Raphael and Holbein because he is a scholar of painting,” Godfrey explains, “and he’ll refer to Lauryn Hill because he’s a person in the world.”

Marshall himself describes beauty shops and barbershops as more than service businesses: they are social hubs, healing spaces, and sites of transformation. “People go in and they come out transformed: they come out polished, they come out made up, they come out done,” he said at a preview of the show. His Chicago neighborhood inspired him—around the corner from his studio is a beauty school offering classes in cosmetology and manicuring. He observed, absorbed, and translated that environment into a work that belongs, visually and thematically, to the canon of great salon and café scenes—from Manet’s Parisian bars to Seurat’s Sunday parks—while radically revising the cast. Here, every figure is Black.

Dialogue with the Past: De Style and Dutch Modernism

Marshall has long been interested in inserting Black subjects into art history. School of Beauty, School of Culture is in direct conversation with his earlier work De Style (1993), which depicts a Black barbershop. The title references the Dutch modernist movement De Stijl, founded by Piet Mondrian in 1917, famous for its grids of primary colors. Marshall borrowed Mondrian’s palette and abstract geometry to elevate an ordinary scene into high art.

In De Style, the barber’s hand echoes a Christ-like gesture, suggesting the spiritual weight these spaces carry in African American communities. By returning nearly two decades later to paint School of Beauty, Marshall completed a kind of diptych: barbershop and beauty salon, masculine and feminine spaces, both essential to Black life.

Community Hubs and Cultural Memory

Beauty salons and barbershops have long been pillars of African American culture. They are places where style is perfected, but also where news is exchanged, politics debated, and support networks forged. Writers and filmmakers—from Inua Ellams’s 2017 play Barber Shop Chronicles to British-Jamaican painter Hurvin Anderson’s barbershop paintings—have treated these spaces as microcosms of Black society.

Marshall taps into that lineage but expands it. His salon isn’t just a room full of women doing hair—it’s a gathering of histories, aspirations, and cultural references. The figures are varied: poised women, playful children, men congregating in the background. They are surrounded by images of Black icons and products, echoes of hip-hop and R&B, and hints of art-historical masterworks.

Anamorphosis and Sleeping Beauty: Holbein in the Hair Salon

The most startling detail lies in the foreground: a distorted yellow shape that seems almost out of place. Look closely—or, better yet, use a camera phone to view it from the side—and you’ll recognize Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty. Marshall has borrowed a technique from Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors (1533), which famously hides an anamorphic skull on the floor between two diplomats. In Holbein’s work, the skull serves as a memento mori—a reminder of death lurking beneath wealth and status.

In Marshall’s painting, Disney’s princess represents something equally insidious: the omnipresence of white beauty standards. A curious toddler examines the distorted figure, hinting at the subtle ways such ideals infiltrate Black spaces and shape self-image. Godfrey notes, “In that painting, Holbein was thinking about how their lives were haunted by death. Kerry uses that idea to think about how white standards of beauty might intrude upon the beauty salon.”

A Scholar of Painting, a Citizen of Culture

Marshall’s paintings are dense, packed with references from art history, pop culture, and Black life. “I’m always trying to make the densest, most compact, complicated pictures I can make,” he says. “More is more.” This maximalist approach invites viewers to spend time decoding.

He’s not content to make work that is merely representational or decorative. By borrowing Renaissance techniques and embedding Disney characters, he refuses to let high and low culture remain separate. He collapses boundaries between the museum and the neighborhood beauty parlor, between Holbein and hip-hop.

The Importance of Scale and Presence

The monumental size of School of Beauty is not just a matter of spectacle. Scale has historically been used in Western art to convey importance: think of the vast history paintings of Jacques-Louis David or the mural-sized canvases of Diego Rivera. By painting Black subjects on such a scale, Marshall insists on their centrality in the cultural narrative.

Before artists like him, Black figures were often absent from major museum walls or relegated to stereotypes. His works—whether portraying lovers, homeowners, or children playing—normalize Black life as worthy of epic treatment. As Godfrey observes, “What he challenges is the fact that Western art museums haven’t, until recently, had large-scale paintings featuring Black people.”

A Career of Rewriting Histories

Marshall’s retrospective at the Royal Academy traces his journey from his early explorations of civil rights–era imagery to his monumental paintings of Black middle-class life. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955, Marshall grew up during segregation and the civil rights movement. His family later moved to South Central Los Angeles, where he witnessed the Watts Rebellion in 1965. These formative experiences informed his lifelong commitment to representing Black life with dignity and nuance.

His breakthrough works in the 1980s and 1990s used deep, nearly silhouetted figures—rendered in shades of black so rich they absorb light—to reclaim Black bodies from caricature. Over the decades, Marshall has painted tender domestic scenes (Past Times), historical allegories (Our Town), and explorations of Black romance (Vignette series).

Revisiting Beauty and Culture

In School of Beauty, School of Culture, Marshall synthesizes these interests: history and modernity, intimacy and grandeur. The salon’s name itself is a pun, echoing traditional “schools” of art while referencing beauty schools that train cosmetologists. The title reminds us that culture is not only made in universities and museums but in small businesses, barbershops, and homes.

The work also suggests a question: What counts as culture, and who gets to decide? By placing Black women and children at the center of a vast canvas, Marshall argues that their lives, conversations, and aesthetics are as worthy of reverence as any European court scene.

Critical Reception and Public Engagement

Visitors to the Royal Academy have lingered before the painting, some laughing at familiar details—the tilted hairdryers, the mirrored walls—others standing in contemplative silence as they catch the Disney princess or trace the lines of Holbein’s influence. Critics have noted the painting’s “bewitching” quality: its ability to entertain casual viewers while rewarding those who study it more deeply.

The work has become a touchstone for discussions about representation in museums. It demonstrates that diversity in art isn’t merely a matter of including Black faces; it’s about rethinking whose stories are deemed universal.

Beyond the Salon: Wider Implications

Marshall’s painting also speaks to broader issues: the commercialization of beauty, the legacy of colonialism in global aesthetics, and the resilience of Black culture. The presence of Sleeping Beauty—a white fairy-tale princess—within a Black salon underscores how Eurocentric ideals persist. Yet the salon is vibrant, full of life and laughter, suggesting a space where those ideals can be questioned, reinterpreted, or rejected.

Moreover, the painting reminds viewers that culture is participatory. The women, men, and children in the scene are not passive subjects—they are actors, creators, and curators of their own identities.

Conclusion: An Invitation to Look Closer

School of Beauty, School of Culture is, on the surface, a portrait of a beauty salon. But it is also an essay on art history, a critique of beauty standards, a celebration of Black community, and a declaration of presence. By weaving Holbein and Disney into a Chicago beauty shop, Kerry James Marshall collapses hierarchies and opens new possibilities.

Standing before the canvas, you can hear the chatter of voices, the whir of hairdryers, the laughter of children. Then, if you look again—really look—you’ll find history whispering in the corners: Mondrian’s geometry, Holbein’s skull, Sleeping Beauty’s distorted face, and, above all, Marshall’s insistence that Black life belongs at the heart of art.

The Royal Academy retrospective doesn’t just showcase a painter at the height of his powers. It invites viewers to reconsider the very foundations of culture—who shapes it, who records it, and whose beauty it reflects.

In that sense, the painting’s title is more than descriptive. School of Beauty, School of Culture is itself a lesson, teaching us that culture is everywhere, that beauty is subjective, and that—if we look closely—there is always more than meets the eye.

Leave a Reply