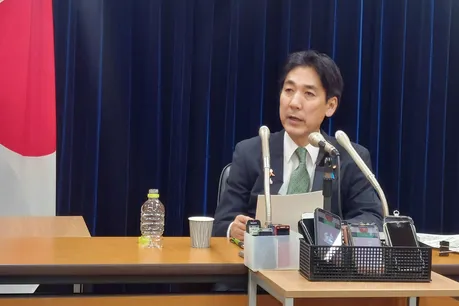

Japan’s new economic agenda is entering a crucial phase as the government prepares to roll out a fresh package of support measures aimed at protecting households and businesses. At the centre of this debate is Minoru Kiuchi who now serves as the minister responsible for coordinating the economic and fiscal policy of the country. He recently made comments that highlight the delicate balancing act facing Japan’s leaders between supporting the economy and maintaining fiscal discipline.

Kiuchi said that when it comes to funding this upcoming package, the government must keep an open mind about all possible sources. Among those options, he did not rule out the possibility of issuing additional government bonds. In his words, while the preference is always to rely on existing revenues and prudent spending, bond issuance remains on the table if circumstances require it.

This is a significant shift in tone. For many years Japan has maintained a strong rhetorical commitment to avoiding large new deficits or bond issuance purely for current spending. The government’s debt level is already one of the highest among advanced economies and public finance watchers have long flagged the risks of further expansion. Against that backdrop Kiuchi’s remark signifies that the government is preparing to accept that supporting the economy may require going beyond conventional funding sources.

Why has this become a pressing issue now? Japan is facing a mix of headwinds. Inflation has persisted above the central bank’s target for some time and import costs are rising thanks to a weaker yen. Many households feel the pressure of higher utilities, stronger global commodity prices and slow wage growth. The new package is meant to address these burdens, shield vulnerable groups and boost medium-term growth through investment in strategic sectors. But the question remains how to pay for it without compromising fiscal credibility.

Issuing bonds is of course one route – it spreads the cost of today’s spending over future years. That can make sense, especially when spending is directed at long-lived investments rather than short-term handouts. But it also carries risks. More government debt means higher interest costs in future, greater exposure to shocks in global bond markets, and less flexibility in responding to future crises. In Japan’s case, given already large debt levels the margin for error is narrow.

Kiuchi’s statement can therefore be read as pragmatic rather than pessimistic. He is signalling that the government does not want to rule out anything in advance because times are uncertain. If growth slows further or inflation remains stubborn, the need to act decisively may override a purely conservative fiscal posture. But he also stressed that issuing bonds is not the preferred first option and that the government will aim to rely on tax receipts, efficient spending and structural reforms where possible.

What market observers will watch closely now is the reaction of bond markets and how yields respond. Japanese government bond yields have already been under pressure as global long-term yields rise and Japan contemplates a larger role for debt. Any loosening of the funding stance may push yields higher, complicating the very calculus the government must manage. Conversely, if investors believe that the issuance will be accompanied by credible growth measures and reform commitments then the risk premium may stay contained.

In short, Kiuchi’s comments mark an important moment in Japan’s policy story. The government is signalling readiness to deploy broader fiscal tools in support of the economy, rather than being locked into a conservative funding doctrine. Whether it proceeds down the bond issuance path and how much it relies on alternative funding routes will be central to Japan’s economic outlook in the coming months.

Leave a Reply